News

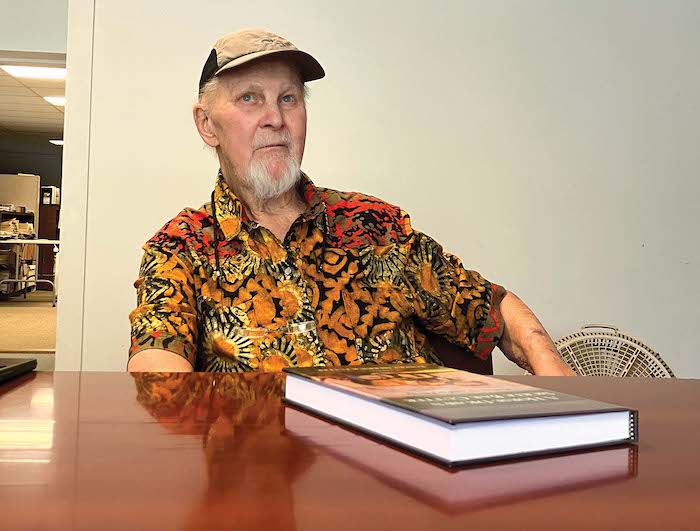

Vermont restauranteur’s new memoir chronicles an adventurous life

Growing up as an academically challenged boy on a hardscrabble dairy farm in central Massachusetts, Robert Fuller couldn’t hardly have foreseen the far-flung and successful course of his life.

What lay ahead for the son and grandson of milk peddlers?

Getting high school grades so poor he was kicked off the football team. Realizing he needed to apply himself, he then made the honor roll.

Next a two-year trip across the nation to Jackson Hole and Los Angeles.

Then a life-altering decision to attend the Culinary Institute of America.

A motorcycle ride through Addison County that later helped convince him to move to Vermont, where he cooked at and owned a series of successful restaurants.

VERMONT RESTAURATEUR ROBERT Fuller traveled well throughout his life, including in 1970 to Florida, where he had good luck fishing one morning,

Photo Courtesy of Robert Fuller

A happy second marriage, world travels, and finally retirement to a lakefront home in Ferrisburgh.

The way ahead for that young boy also included more travel and excitement and happiness — all of which, Fuller, now 79, said, can be traced back to his high school insight that he could master his own destiny.

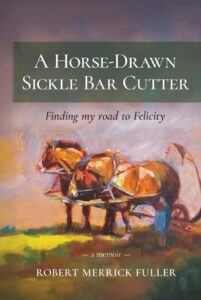

Now the former long-time Lincoln resident has written a self-published memoir, “A Horse-Drawn Sickle Bar Cutter: Finding my road to Felicity.”

“I was able to decide myself how I wanted my life to go, and then I wanted to have adventures. I wanted to travel. A lot of this book is about adventures I had, motorcycling here and there and driving up and down the East Coast, and to California and back, and lots of other activities,” Fuller said. “I’ve been helicopter skiing in British Columbia. I’m just a farm boy from western Massachusetts. The idea of helicopter skiing to me was like going to the moon.”

The first part of Fuller’s title pays homage to a tool his father used to cut hay; it’s also the name of a painting he owns and admires and which adorns the cover of his memoir.

The subtitle refers to his journey to fulfillment that helped spark Fuller’s decision to write nearly 300 pages.

“People should be buying my book who are interested in improving their own place in the world and realizing that you’re in charge of your happiness,” Fuller said.

Fuller believes his story can resonate with others who overcame challenges and found happiness, and those who are dealing with adversity and seek inspiration. Thus he wrote his book, one sprinkled with anecdotes, photos, inspirational quotes, and poetry by himself and others.

As well as finding inspiration, readers might well also enjoy the book’s look at childhood in rural post-World War II America, before technology and organized activities ruled young lives; the details it offers of life in the tumultuous late ’60s and early ’70s; and its insights into the restaurant business.

ON THE PATH

Fuller was born in Ludlow, Mass., on the family farm in 1946, a member of six generations of Fullers to live in the 150-year-old farmhouse. He is also a descendant of Edward Fuller, who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620.

By the time Fuller’s father, Douglas, inherited the farm, he was buying milk from other farms, pasteurizing it, and then bottling it and delivering it to customers, often with Robert riding along. What Fuller called a “fading” business ended when his father died in an accident when Fuller was 12, a traumatic event he recounts in the book.

ALTHOUGH ROBERT FULLER’S father died when Fuller was 12, Fuller, seen here as a child, describes many aspects of his youth on a rural Massachusetts farm as happy. Photo courtesy of Robert Fuller

Although he struggled in school, Fuller until that point describes a happy childhood playing with neighborhood friends in the countryside on and around his farm, making up games in the days before television, never mind cellphones and the internet. It was a free-range childhood.

But Fuller said he failed second and seventh grades “mostly because I was lazy,” and three Fs on his sophomore report card at least temporarily derailed his football career.

“That’s what really woke me up. I said I’ve got to do better than that,” he said. “Eventually I started making the honor roll.”

He kept aiming high and was elected senior class president.

“Having this kind of academic success … starts to make you feel good about yourself. You get this feeling, ‘Oh, I want more of that,’” he said.

College didn’t appeal, and for a time Fuller took a blue collar jobs. He read an article about careers that didn’t require an academic degree. One possibility caught his eye: “They had a picture of a guy with a white coat and a tall hat; you know, culinary arts.”

In 1969 he entered the Culinary Institute of America, then in New Haven, Conn., and completed its program in 1971.

After growing up on “hot dogs and hamburgers,” it was eye-opening and exciting.

“It introduced me to a lot of food I’d never heard of,” Fuller said. “The first week I was there I went out with another student to a diner restaurant in downtown New Haven, and they said, ‘What are you going to have?’ And he said, ‘I’m going to have the lasagna.’ I didn’t know what lasagna was.”

Soon he discovered many other exotic dishes and his favorite, French cuisine.

“I loved learning about international cooking,” Fuller said.

In the fall of 1971, he and a girlfriend packed up a van and headed to Jackson Hole, Wyo. After a year, his girlfriend went back to college in New England, and Fuller headed to Laguna Beach, Calif., with a pottery instructor to work in her studio, and he also found restaurant work.

“I sold my van, I let my hair grow, and I bought Earth Shoes,” Fuller said.

After a year in LA he yearned to return home. He drove back east via Wyoming to pick up a tepee that he had left there and still owns. Fuller ran into talk show host Dick Cavett while doing so, an encounter he illustrates in the book with a photo.

ON TO VERMONT

Back in Massachusetts, he worked in a French restaurant, and then in a steak house in Springfield. He also tells of taking a motorcycle trip to Montreal to see Expo 1967 and coming back through Middlebury and being charmed.

In 1975 the assistant manager of the steak house he worked at was Marty Schuppert, who four months later left to manage Mister Up’s in Middlebury. In January 1976 Schuppert persuaded Fuller, then 29, to join him as the chef.

“As soon as I got here I realized this was where I wanted to live,” Fuller said.

He stayed at Mister Up’s until May of 1982, when Fuller bought Pauline’s Restaurant on Shelburne Road in South Burlington and learned how to run a business from soup to nuts.

THE COVER AND title of Robert Fuller’s new memoir honor his rural farming heritage and what he calls his determination to master his own destiny and find happiness and success.

“I just went to work. I figured it out,” he said of a restaurant he operated successfully for 26 years.

From there, the restaurant dominoes fell. Only one domino, Deja Vu in Burlington, which he bought in 1986, didn’t fall properly. Fuller said a few factors, including an economic slowdown, hurt the venture. Thus, he sold for a loss in 1992, while at the same time seeing his first marriage end.

Fuller bounced back personally and professionally. In December of 1992 he met his now wife, Alison Parker, at a party in Lincoln, their home town, and within six months they were living together. They celebrated their 30th weeding anniversary in June.

In the mid 1990s Fuller put an addition on Pauline’s and business increased dramatically. In 1997 he bought Leunig’s Bistro in downtown Burlington, and he writes it became the “most successful restaurant” in Vermont. He operated Leunig’s for 16 years and Pauline’s for 26 years, before taking his “official retirement” in 2013.

BRISTOL

Before then Fuller set his sights on Bristol. He and partner Drew Smith bought Cubbers in 1998. Before retiring he also teamed with partners to buy the Bristol Bakery and Snap’s Restaurant. Smith’s 2001 remark to Fuller that there was no place in Bristol to just get a burger and a beer with friends sparked the creation of The Bobcat Café on Main Street.

“It’s the only one I ever built from scratch,” Fuller said. “All the other ones somebody else started, and I reformatted them a little bit.”

Fuller eventually sold The Bobcat a half-dozen years into its existence, and it remains successful — as do, according to his book, the other Bristol ventures in which he held an interest.

What makes a successful restaurant?

He said food, location, parking and even lighting all matter, but there is more. He likened the work of a restaurant to “a theatrical performance where the audience gets to eat some of the props.”

“The food has to be good, and it has to be consistent. You can’t have a good meal one time and a bad meal another time. People don’t like to gamble with their dining dollars. But with little restaurants like Pauline’s and the Bobcat, it’s all about the people.”

Fuller also writes about happy hours spent biking, whitewater canoeing and kayaking, skiing and traveling to Ghana and Europe, and dining in restaurants with Michelin Stars, including one near Cannes, France.

“I remember sitting there thinking, look at me, this farm boy sitting in a three-star restaurant in France,” he said. “I’ve had a lot of those sort of adventures, which I’ve loved.”

In his chapter on retirement, he quotes a speech from Winston Churchill, another indifferent student: “Never give in, never give in, never, never, never.”

Fuller relates to that sentiment. A passage in his chapter on retirement notes he ranked 107th out of 210 students in his high school class.

“It doesn’t get any more average than that. I’m a very average guy,” he wrote “The only thing that saved me was my willingness to work.”

“A Horse-Drawn Sickle Bar Cutter: Finding my road to Felicity” is available at the Vermont Book Store; Phoenix Bookstore in Essex, Burlington and Rutland; and, if necessary, online.

Fuller’s first book launch is planned for the Lincoln Library on Sept. 4 at 6 p.m. It will be a joint effort with Louella Bryant. Fuller will read from his memoir, and Bryant will read from her memoir, “Hot Springs and Moonshine Liquor.” Light snacks and soft drinks will be served.

More News

Homepage Featured News

Leicester farmer launches state Senate bid

Hannah Sessions, Co-Owner of Leicester’s Blue Ledge Farm, is running for one of the two st … (read more)

News

Education, healthcare and land use reform dominate Legislative breakfast

VERGENNES — Healthcare reform, new land-use protocols and an ongoing revamp of Vermont’s p … (read more)

News

Two seek ACSD seats; two have no takers

Two of the four looming vacancies on the Addison Central School District board have failed … (read more)